entangled bodies in a tree drawings

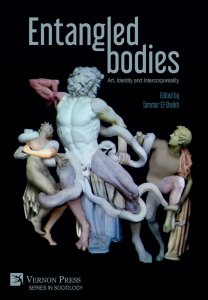

Joshua Shaw reviews Entangled Bodies: Art, Identity and Intercorporeality, ed. Tammer El-Sheikh (Malaga: Vernon Press, 2020).

Organ transplantation challenges social and legal theories that have historically insisted upon clear boundaries between human individuals (Shildrick 2012; 2015; also see Mykitiuk 1994), inviting us to understand and act as if our bodies as interconnected. The presumed limits of our bodies are thereby disrupted with heart transplants. But these encounters with transplant technology are also ontogenetic, as Gilbert Simondon would put it (Lapworth 2016), radically re-articulating the corporeal and physical processes that make up what we encounter, experience and recognise as the human body. These ruptures are not just metaphorical; the process of extracting viable, complex tissue from one human body and grafting it in the next invites metaphor to apprehend the technological feat, but these ruptures go deeper in the sense of our material being or ontology. It is these ruptures that are at the heart of Entangled Bodies: Art, Identity and Intercorporeality, edited by Professor Tammer El-Sheikh of York University and published by Vernon Press, which documents and explores the corporeal mess of heart transplantation in a series of essays.

Feminist scholars of the body have long contested the presumed separation of individual bodies, conceptualising the relationality which undergirds social and material forms. This relationality can, in part, be understood as our interdependence and connection. Carol Gilligan (1982), for example, argued that women tend to behave according to an ethic of care sensitive to human interdependence and connection, in contrast to the individualising, masculine forms of moral psychology that take these relations for granted. Attention to the interdependence and connection of human bodies has since become a familiar feminist intervention in medical law and ethics, such as in the work of Jocelyn Downie and Jennifer Llewellyn (2008; 2011), revising ethical principles like autonomy with respect to differences of power expressed relationally through medical practice and public health which are often gendered, racialised, sexual, generational, etc. But material, corporeal feminists go farther in grasping this relationality as a challenge to the ontological status of the human body; the presumed limits of individual bodies are fictions concealing a much messier reality (Kazimierczak 2018). Instead of reaching a limit at our fingertips or elsewhere on the skin's surface, our bodies, as Stacy Alaimo (2010) puts it, are porous, extending, entangling with everything around, inside and outside that that we recognise as self and other. Drawing from the phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1968), all bodies are emplaced and find expression from within a social flesh, which extends from such bodies and yet mediates connection and effects between them. Margrit Shildrick, one of the contributors of Entangled Bodies, has long explored this material sense of relationality in the context of critical body and disability studies, reading bodies' "leakiness" as mediating cultural constructions of some bodies as monstrous and in need of regulation (see e.g., Shildrick 1997). Shildrick, like other material, corporeal feminists, have theorised post-conventional expressions of bioethics attendant to this ontological relationality, not according to pre-determined norms such as autonomy, but rather provisionally and situationally, immanent to the dynamic relations of vulnerability and power of our leaky bodies (see e.g., Shildrick & Mykitiuk 2005).

Feminist scholars of the body have long contested the presumed separation of individual bodies, conceptualising the relationality which undergirds social and material forms. This relationality can, in part, be understood as our interdependence and connection. Carol Gilligan (1982), for example, argued that women tend to behave according to an ethic of care sensitive to human interdependence and connection, in contrast to the individualising, masculine forms of moral psychology that take these relations for granted. Attention to the interdependence and connection of human bodies has since become a familiar feminist intervention in medical law and ethics, such as in the work of Jocelyn Downie and Jennifer Llewellyn (2008; 2011), revising ethical principles like autonomy with respect to differences of power expressed relationally through medical practice and public health which are often gendered, racialised, sexual, generational, etc. But material, corporeal feminists go farther in grasping this relationality as a challenge to the ontological status of the human body; the presumed limits of individual bodies are fictions concealing a much messier reality (Kazimierczak 2018). Instead of reaching a limit at our fingertips or elsewhere on the skin's surface, our bodies, as Stacy Alaimo (2010) puts it, are porous, extending, entangling with everything around, inside and outside that that we recognise as self and other. Drawing from the phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1968), all bodies are emplaced and find expression from within a social flesh, which extends from such bodies and yet mediates connection and effects between them. Margrit Shildrick, one of the contributors of Entangled Bodies, has long explored this material sense of relationality in the context of critical body and disability studies, reading bodies' "leakiness" as mediating cultural constructions of some bodies as monstrous and in need of regulation (see e.g., Shildrick 1997). Shildrick, like other material, corporeal feminists, have theorised post-conventional expressions of bioethics attendant to this ontological relationality, not according to pre-determined norms such as autonomy, but rather provisionally and situationally, immanent to the dynamic relations of vulnerability and power of our leaky bodies (see e.g., Shildrick & Mykitiuk 2005).

The ontological ruptures of transplantation reinforce material, corporeal feminists' conception of our porous bodies in this general sense. But the specific relations at work in the context of heart transplants, as shown throughout Entangled Bodies, push us to revisit corporeal experience with respect of the physical composition of our body and an organ—the heart—that has been understood for centuries as the site of the soul, self, etc (Shildrick 2015). Against medical research affirming the efficacy of the surgical procedure (e.g., quantitative "quality of life" indicators) and that treat the graft as the mere act of changing in a spare part, Entangled Bodies lay out the corporeal hybridity for all to see: the death averted by the death of another, the incorporation of tissue whose genetic basis will never be that of its host, and the corresponding need to take medications for the remainder of one's life to keep the body from rejecting the graft.

At the heart of Entangled Bodies are qualitative research projects that tap into the corporeal experience of heart transplant recipients and families of donors. Those projects—known collectively as "Hybrid Bodies"—were comprised of two research groups: "The Process of Incorporating a Transplanted Heart" (PITH) and "Gifting Life: Exploring Donor Families' Embodied Responses to Anonymous Organ Donation in Canada" (GOLA) (p. ix). These projects were qualitative, using embodied methods of interviewing to encounter gestures and feelings among other affects, which often contrasted with interviewees' verbal reports, revealed complicated identifications and otherwise challenged how medical researchers have understood the impact of transplant technologies (see e.g., Abbey et al. 2011; Mauthner et al 2015; Poole et al. 2011; Poole et al. 2016; Ross et al. 2010). Hybrid Bodies also included artists and curators who, based on the qualitative findings from PITH and GOLA, created and exhibited works that imagined the consequences of heart transplantation for human bodies, including identities and ethico-political relations formed with others rendered possible through the transplant. Medical-arts interventions thereby facilitated theoretical and speculative expansions upon the empirical findings from PITH and GOLA, complementing the philosophical output of Margrit Shildrick (e.g., 2012; 2013; 2015), and expanding communicatively the reach of Hybrid Bodies. Such a sustained and in-depth collaboration among a coterie of researchers, artists, curators, etc. is rare, if not unique, and, accordingly, merits reflection (e.g., Shildrick et al. 2018). Entangled Bodies provides such reflection; the essays compiled in Entangled Bodies are—with exception of Donna McCormack—authored by contributors to Hybrid Bodies' various research and artistic projects, expanding from the methodological focus of the groups' prior reflections to attend to the personal, aesthetic and philosophical aspects of undertaking transdisciplinary work, as well as meditations on the corporeal experience of organ transplantation.

Tammer El-Sheikh writes that, in editing this volume, it was important to "[represent] Hybrid Bodies as a mobile and expansive entity, with constituencies in various fields, on several continents, and across a spectrum of abilities" (p. xii). Indeed, Entangled Bodies succeeds in establishing this nomadic status. First the reader is introduced to PITH through the personal account of Heather Ross, a physician and surgeon and PITH's principal investigator. Her account diarises the process by which the core research problem emerged (i.e., "the 'picture' perfect concept of life post-heart-transplant was fraught with challenges that we had previously been unaware of" (p. 7)), and the epistemological anxiety of confronting qualitative, transdisciplinary and arts-based research and knowledge translation for the first time through Hybrid Bodies. With this core problem identified, Ingrid Bachmann pulls us away from the surgical table to ponder classical sculpture, African carvings and the mutilated faces of soldiers of the First World War alongside the hearts of patients in need of a heart transplant, and how these archaeological and medical encounters each evoke a narrative that "damaged bodies [are] in need of repair" (p. 13) to some original, authentic state. Evaluation of each depends upon the achievement of "invisible mending" (p. 14), in which the process of repair is disappeared. The (seemingly inevitable) consequence of hybridity is thereby denied through these narratives despite the real ontological difference produced through methods of repair. Uncovering and attending to this difference, despite what regulatory regimes insist upon, has been the principal object of Hybrid Bodies. The first part of the volume then concludes with Hannah Redler Hawes exploring the "curatorial work-in-progress" of Hybrid Bodies, including past and future exhibitions of the artist-scholar collaboration, "reflective interpretation[s] of nearly 20 years' [of] work" (p. 23) from the project's artists and scholars, and observations of how "audiences [of past exhibitions] [became] [and future audiences undoubtedly will become] wrapped up in like emotions, like quandaries, like experiences" (p. 29) despite not necessarily having experienced a heart transplant. The following three parts of the volume follow this structure, flowing from experience to theory to the speculative creation, to address concepts of corporeal hybridity, listening and the place, space and location of heart transplantation.

Entangled Bodies culminates in challenge as hybridity perfuses the text itself. The juxtaposition of experience, theory and art forms affective, creative lines of flight at the chapters' seams, grafting together representation and the volume's materiality with particular effect. These lines of flight pull the reader out from a seat of comfort to consider unanticipated directions. In other words, El-Sheikh's editing produces a porous flux of interventions and meanings—personal and impersonal, direct and indirect—that reinforce the hybridity the contributors' chapters attempt to represent and explain, leaving the reader unsteady, teetering in the effort to make sense. Far from a position of disadvantage, this unsteadiness encourages humility in the reader and, accordingly, room to grapple with the ontogenetic ruptures of heart transplants. These ruptures capture more than the donor-recipient relations proper, such as the research process relative to heart transplants themselves, the place of art in research and, more generally, ways of relating that could be formed from transplants. The reader then cannot escape disruption to the ontological bounds of the human body, the cultural meaning of healing and the composition of the research apparatus, among other themes. The reader is ensnared in the very "messy entanglements" (Shildrick et al. 2018) between the researchers and artists of Hybrid Bodies. From the middle of this tangle, we may thereby be inspired to encounter heart transplants—and our relations more broadly—differently, playing with the chimaeric traversals and re-combinations of scholar-art interventions.

*****

Entangled Bodies: Art, Identity and Intercorporeality (2020), ed. Tammer El-Sheikh, is published by Vernon Press.

Joshua Shaw is a PhD student at Osgoode Hall Law School, York University, in Toronto, Canada. His dissertation is on law's relations to human remains, whilst his research, generally, pertains to the regulation of bodies and health. His most recent peer-reviewed publication is "Confronting Jurisdiction with Antinomian Bodies," which was published in Law, Culture and the Humanities:https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1743872120942770

Additional works cited:

Abbey, Susan E, Enza De Luca, Oliver E Mauthner, Patricia McKeever, Margrit Shildrick, Jennifer M Poole, Mena Gewarges and Heather J Ross. 2011. Qualitative interviews vs standardized self-report questionnaires in assessing quality of life in heart transplant recipients. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 30(8): 963-966.

Alaimo, Stacy. 2010. Bodily natures: Science, environment, and the material self. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Downie, Jocelyn and Jennifer Llewellyn. 2008. Relational theory and health law and policy. Health Law Journal 16: 193-210.

Downie, Jocelyn and Jennifer Llewellyn, eds. 2011. Being relational: Reflections on relational theory and health law. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Gilligan, Carol. 1982. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women's development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kazimierczak, Karolina A. 2018. Clinical encounter and the logic of relationality: Reconfiguring bodies and subjectivities in clinical relations. Health 22(2):185-201.

Lapworth, Andrew. 2016. Theorizing bioart encounters after Gilbert Simondon. Theory, Culture & Society 33(3): 123-150.

Mauthner, Oliver E, Enza De Luca, Jennifer M Poole, Susan E Abbey, Margrit Shildrick, Mena Gewarges and Heather J Ross. Heart transplants: Identity, disruption, bodily integrity and interconnectedness. Health 19(6): 578-594.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1968. The visible and the invisible. Evanston, US: Northwestern University.

Mykitiuk, Roxanne. 1994. Fragmenting the body. Australian Feminist Law Journal 2: 63-98.

Mykitiuk, Roxanne and Margrit Shildrick, eds. 2005. Ethics of the body: Postconventional challenges. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Poole, Jennifer, Jennifer Ward, Enza De Luca, Margrit Shildrick, Susan Abbey, Oliver Mauthner and Heather Ross. 2016. Grief and loss for patients before and after heart transplant. Heart & Lung 45(3): 193-198.

Poole, Jennifer M, Margrit Shildrick, Enza De Luca, Susan E Abbey, Oliver E Mauthner, Patricia D McKeever and Heather J Ross. 2011. The obligation to say 'thank you': Heart transplant recipients' experience of writing to the donor family. American Journal of Transplantation 11(3): 619-622.

Ross, Heather, Susan Abbey, Enza De Luca, Oliver Mauthner, Patricia McKeever, Margrit Shildrick and Jennifer Poole. 2010. What they say versus what we see: "Hidden" distress and impaired quality of life in heart transplant recipients. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 29(10): 1142-1149.

Shildrick, Margrit. 1997. Leaky bodies and boundaries: Feminism, postmodernism and (bio)ethics. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Shildrick, Margrit. 2012. Imagining the heart: Incorporations, intrusions and identity. Somatechnics 2(2): 233-249.

Shildrick, Margrit. 2013. Re-imagining embodiment: Prostheses, supplements and boundaries. Somatechnics 3(2): 270-286.

Shildrick, Margrit. 2015. Staying alive: Affect, identity and anxiety in organ transplantation. Body & Society 21(3): 20-41.

Shildrick, Margrit, Andrew Carnie, Alexa Wright, Patricia McKeever, Emily Huan-Ching Jan, Enza De Luca, Ingrid Bachmann, Susan Abbey, Dana Dal Bo, Jennifer Poole, Tammer El-Sheikh and Heather Ross. 2018. Messy entanglements: Research assmeblages in heart transplantation discourses and practices. Journal of Medical Humanities 44(1): 46-54.

Source: https://thepolyphony.org/2021/01/25/entangled-bodies-art-identity-and-intercorporeality-book-review/

0 Response to "entangled bodies in a tree drawings"

Post a Comment